Have you just started grad school? Does it seem scary? Fear not, young Padawan – below you’ll find guidance on your road to PhDoom.

(Disclaimer – this is yet another list. The internet is full of them. You don’t have to read it. And more importantly, you don’t need to follow the advice. I wrote the list today mainly because I was bored and tired after handed in a giant application yesterday, and after spent the major part of the night awake with a sick child).

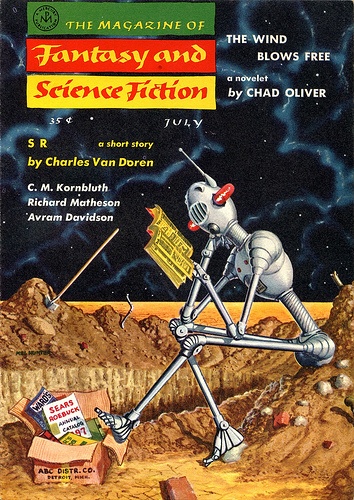

1. Read the god damn literature

You’ll be surprised how much knowledge there already is out there. The Great Idea you want to test in your thesis likely has been thought many times before, and chances are that it has already been tested by others. A professor at my former university used to remind graduating students about the repetitiveness of science by handing over old books (like 19th century books) on the exact subject of the thesis during the dissertation party. Hence, the best advice I can give is to plow the relevant literature in your field. Follow the references to the original sources, and learn first hand. There are no shortcuts.

2. Get some friends

You may feel lonely at first. It is all new and it feels like everyone is smarter than you. Don’t despair, get some friends instead. Academia is a great place to get to know other people, in your laboratory, in the cohort of PhD students and postdocs, and with the faculty folks (although they are generally more dull). Think of them as your hive mind – knowledge to gain, and knowledge to share. Don’t lock yourself inside your room – go have a coffee with the others (see Swedish fika), have a beer (or coke) at after work sessions, go birdwatching, go whatever as long as it makes you connect with your colleagues. And another free advice: everyone thinks that everyone else is smarter, it is the impostor syndrome – a widespread epidemic in academia – just try to get over it.

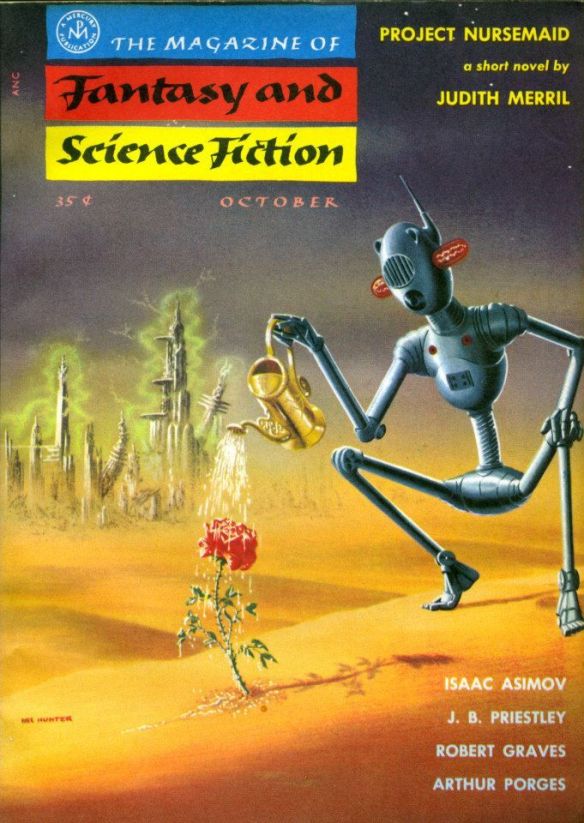

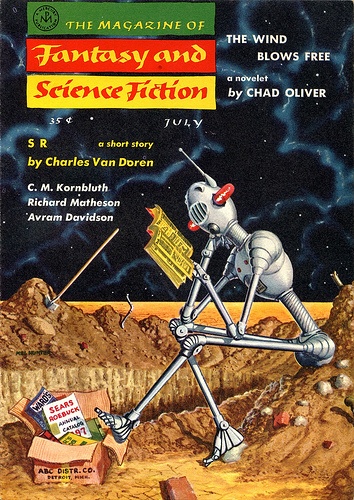

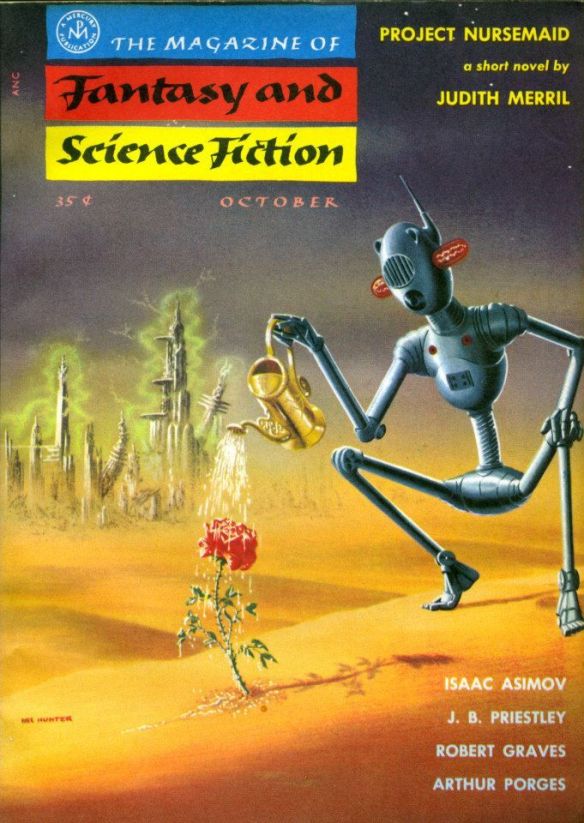

3. Water that plant

Water that plant, and watch it grow.

Science is a gradual process. There are the occasional big leaps, but generally it is a slow and tedious ride. Have patience, water your manuscript plant every day and after a few weeks, months, or a year, from now it will be a flowering plant published in a glossy magazine. You can not cut corners, science has to be done thoroughly, or not at all.

4. Broaden your perspectives

Try to get out of your box, your comfort zone. Read studies that don’t relate immediately to your own field. Go to seminars about jelly fish, CRISPRs, dinosaur teeth, or sexual selection – it is a great privilege to have the ability to listen to other peoples’ talks. Use that.

Furthermore, you SHOULD visit conferences and/or other research groups during your PhD studies. This is something your supervisor should help arrange, and most importantly pay for. You. Need. To. Travel. And. See. Places.

5. Broadcast your findings

Tell the world of your findings! In a conference, on social media, to your grandma, to your cat, to the strangers on the bus – spread your gospel. You could even start a blog…

Importantly, if you believe your findings have a relevance for society at large YOU are the one best suited to broadcast that information. I can guarantee you that policymakers will not read your scientific articles, even if they are printed in high impact journals. Thus, if you have a message it needs to be put forward in the right forum. This is a responsibility that comes with being an expert.

6. Have a social life

In order to function at work we need to have a life that stretches beyond the university offices. Well, this is advice most people don’t need – most students engage in a range of social activities. But over the years I have met people that always work, and never do anything non-sciency. They often break down in the final year.

And social life does not need to be binge drinking.

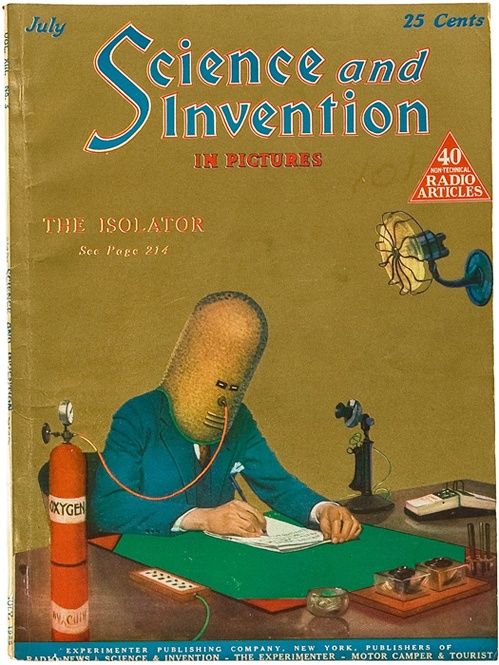

7. In the end, focus

Remember to breath.

The last stretch of a PhD is writing, writing, and writing. For some even #madwriting. You need to produce a thesis, and the last months are a major undertaking for everyone. In order to make it bearable, make a time line and stick to it. Inform your supervisor(s) and co-authors when to expect drafts of chapters and manuscript, and make sure to follow up associated deadlines. Supervisors are humans, too. Giving a full thesis to read over the weekend is not a precious gift.

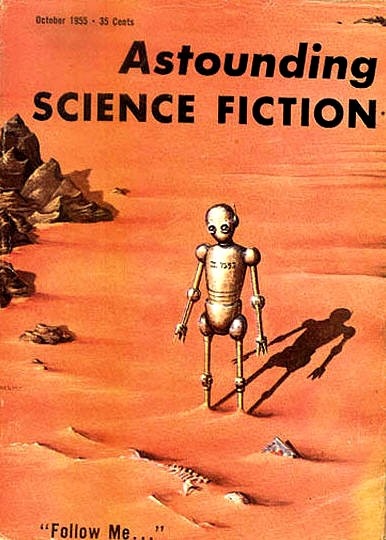

8. Have a mock defense

Don’t fear the thesis.

One of the best advice I can give you is to have a mock defense before the real one. Let your friends and colleagues pepper you with questions. Ask them to play the role of the panel, and do it as realistic as possible. You’ll be surprised how well this little exercise can help chase the thesis demon away.

9. Choose your thesis panel with care

Each country has their own system, but normally there is some sort of appointed committee that will read and evaluate your thesis. In the Swedish system the opponent (external examiner) has a big role, where he/she discusses the merits of the thesis in an open session. The choice of opponent has great bearings on how the thesis defense will play out, so discuss this carefully with your supervisor. If your goal is to continue in science, a good advice is to choose an opponent in which lab you would like to do a postdoc. Just sayin’.

10. Make plans, and keep to them.

You can do wonders in life, and a PhD is a bridge to the future, not a dead-end street. Too many students think of post-PhD life as a black hole filled with unemployment and broken dreams. In reality it is often not, but one has to be realistic about the prospects of different career paths. To get a tenure faculty position is hard, and requires skill, heaps of luck, and a vagabond lifestyle for some years ahead. But most people will not carry on in science, and you have to see the non-academic path as excellent alternative, not as a failure. Halfway through grad school is probably a good time to start think about the future, and to plan for how those dreams should be fulfilled.

12. Enjoy the show

I don’t say it is easy, because it isn’t, but try to enjoy the final show. It is the culmination of a lot of hard work and you get the chance to show the world how good you are in your field. And that is pretty amazing, after all.