How to infect a duck?

A critical parameter for the spread of a pathogen is the mode of transmission. Some pathogens have evolved to use mosquitoes or ticks as transmission vectors; others rely on direct contact, such as via body fluids during sex, and a score of pathogens travel by air, water or soil to reach the next host. Which route that is optimal depends on the interplay between the pathogen, the host(s) and the environment they occupy.

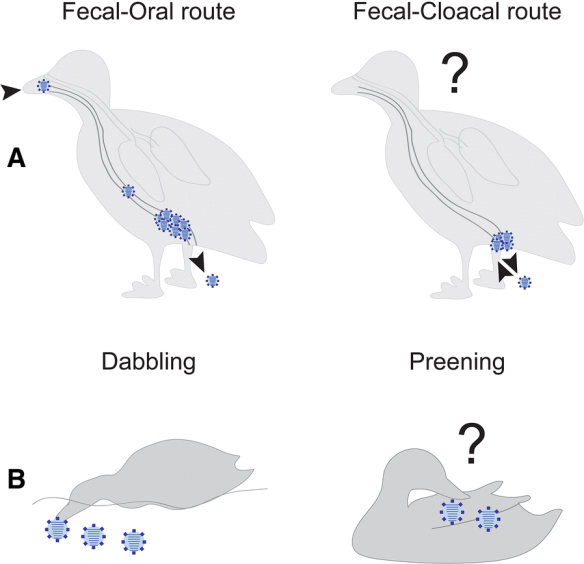

If we think about ducks, it makes sense to consider water as an effective medium for pathogen transmission. This indeed the case for several duck pathogens, and perhaps most notoriously for low-pathogenic avian influenza viruses. In ducks these viruses are common, causing mild gastrointestinal infections, and infected virus particles are shed in high numbers in feces. The conventional wisdom has been that the fecal-oral infection route is the most important, strengthen by the feeding habits of dabbling ducks where they skim the surface for food items, thereby exposing themselves for newly excreted viruses from their ducky friends.

But if you look yonder, at the ducks bobbing around in the pond, you will notice that they do other things as well. Of course, they dabble their bills in the surface waters, but they occasionally stretch the head and neck down to nibble at food stuff further down in the water. To keep the plumage nice and clean – and their bodies dry – they spend a significant proportion of their time carefully preening their feathers.

Such observations have resulted in alternative infection mode hypotheses, but until now we haven’t been able to disentangle them. In a seminal publication, Wille and co-workers at Uppsala University tested to what extent low-pathogenic avian influenza viruses can infect mallard ducks via the process of cleaning their feathers, or via the rear end, in a process called ‘cloacal drinking’. The drinking part refers to that when pressures are posed when ducks poo, it may create a vacuum through which a little volume of water enters the cloaca, which if containing influenza virions may cause an infection in the lower intestinal tract, bypassing the more traditional mechanism of swallowing viruses.

The paper is essentially an ‘how to infect your duck’ guide, complete with some clever appliances and boxes, and rounds of disinfections, to clearly separate the different modes of infection. And, yes, there are indeed many ways to infect a duck, as both preening and cloacal drinking also resulted in infections. Overall It is time for broadening our view of possible infection routes for flu, and other pathogens, especially those that are transmitted through water.

Link to the paper: